Welcome! I’m Richard Schwartz, a retired high school Social Studies teacher from Morristown, New Jersey. In “Common Sentences” I’ll share my thoughts on history, sports, popular culture, politics, religion. I hope you’ll find it engaging.

On January 11, 1776, Thomas Paine, an English immigrant to Pennsylvania, published Common Sense, and changed the course of history.

But even if that pamphlet played perhaps the greatest role in swinging colonial public opinion to independence, and even if it caused many people to begin thinking of themselves as Americans rather than Britons, Paine has never made it big. No currency bearing his hawk-nosed likeness. No Broadway musicals. No play-by-play man ever says to Bill Raftery, “Coach, the Fighting Penmen of Thomas Paine University are looking to pull a major upset in this first-round game with mighty UCLA. Can they do it?” Hardly anyone came to his funeral.

Teddy Roosevelt, ever Mr. Subtle, famously reviled Paine as “a dirty little atheist.” Thomas Edison rejected that and added “I consider Paine our greatest political thinker.”

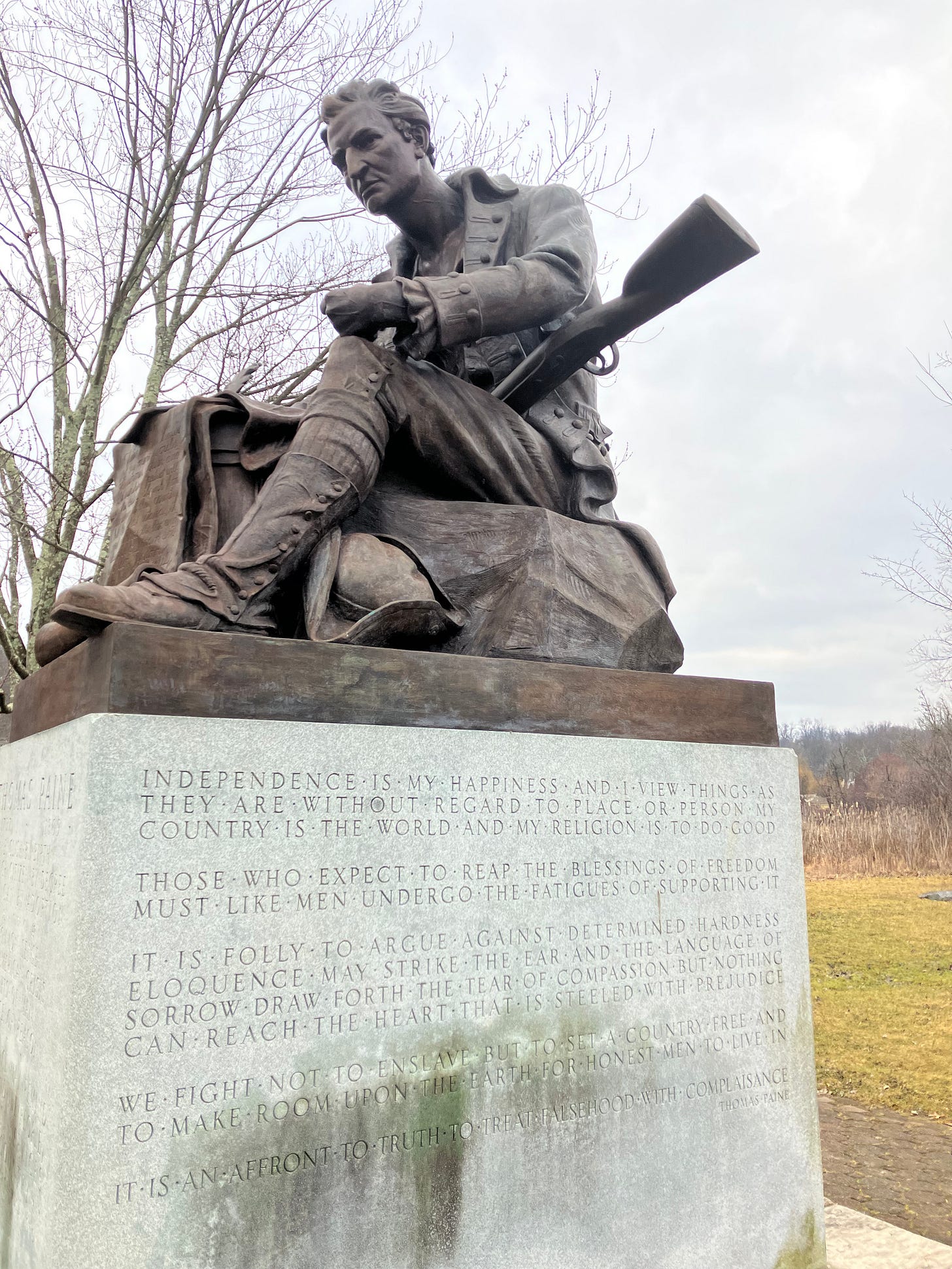

When, in 1950, amid a fear of radicalism, many American towns declined the offer of a statue of Paine by a Danish sculptor, Georg Lober, Morristown, New Jersey said yes. And so we in Morristown have a wonderful monument to the man who, when the Continental Army appeared ready to disintegrate in late 1776, famously wrote a line that alas never seems irrelevant: “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

I always enjoyed devoting a class period to Common Sense. Of course, in the headlong chase to June, one day was all I ever allowed myself.

The fun part of teaching Paine came from Edmund Morgan’s The Birth of the Republic, 1763-1789. I used to issue and teach that short book to my AP US History students. Morgan explained that by January 1776, the colonists:

were on the verge of a discovery that would turn the course of history in a new direction, a discovery that is still reverberating among us and liberating us from our past as it was soon to liberate them, in spite of themselves, from theirs.

That discovery was nothing less than the principle of human equality.

Common Sense, Morgan argued, bought them to that discovery.

Paine went right at George III. He called him “the sullen-tempered Pharoah,” “the royal brute” of Great Britain, and asked how this tyrant could sleep at night with the blood of so many of his subjects on his hands.

But Paine hunted bigger game. He wanted to blow a hole through monarchy as an option for the independent American nation that he foresaw emerging from the war. Do we believe that all men are created equal, asked Paine? Then can someone explain to me why we would ever accept a king? You can either have equality or you can have monarchy, argued Paine, but you cannot have both.

When the Constitution’s framers, eleven years later, decided that a single, unitary executive, a President of the United States was necessary, they bypassed Alexander Hamilton’s plan for electing a president for life and forbade titles of nobility. Paine as much as any one voice appears to have been responsible for this.

But he also went after hereditary succession. Living under a monarch degrades us, wrote Paine. Hereditary succession means that our children, then our grandchildren, then our great grandchildren live under their own degradation. How is it, he wrote, that one man gets to set his children up in perpetual control of the office? Hereditary succession is a gross violation of equality. The monarch’s offspring are not created equal—they are born with powerful privileges.

In this sense, they’re like “legacies” in our American college admission game. When Students for Fair Admissions’ lawyers argued against Harvard’s and Chapel Hill’s admission policies before a very receptive conservative majority on the US Supreme Court, they focused their attack on race as a ‘plus factor’ among many in admission to American universities. What doesn’t seem to have bothered them as much—though the issue came up—was the violation of Tom Paine’s understanding of equality as the bestowing of unearned privileges on the children of alumni parents (and especially those of well-heeled, big giving alumni mommies and daddies.) This denies spots to deserving, but connectionless applicants.

I’ve seen an awful lot of wonderful high school seniors launch doomed charges on Nassau Hall, College Hill, Morningside Heights, Harvard Yard, New Haven Green, Palo Alto and other treasured destinations and bravely endure seeing the focal point of their K-12 academic lives blown to smithereens by overworked but well-dug-in admissions committees firing grapeshot laced with expressions of regret. To hold out privileged spots for alumni children only makes a college-admissions system already bordering on the abusive downright un-American.

Maybe we need to resurrect Tom Paine’s common sense on equality in the face of privilege and apply it to university admissions.

I'd be interested in your take on "wokeism," and a term I recently learned, "presentism," the practice of judging the conduct of the past by the standards of the present. I see a lot of this here in VA, where Jefferson is currently so reviled for being a slave owner that the Thomas Jefferson Regional Health District was renamed the Blue Ridge Regional Health System just so his name didn't have to appear.