https://www.gettyimages.in/detail/news-photo/eastern-regional-playoffs-princeton-bill-bradley-in-action-news-photo/83384499?adppopup=true

Last Thursday, Princeton stunned mighty Arizona in the first round of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament; the Tigers defeated Missouri on Saturday. Toss that in with FDU’s Friday defeat of Purdue and last year’s run by Saint Peter’s and the Garden State sends a message for future national championship aspirants from the Big Ten, Pac 12, ACC, Big East or SEC: pray you don’t draw a Jersey minnow in the first round.

Thursday night, after the Arizona upset, The New York Times’ Scott Miller likened Princeton’s late go-ahead basket off an assist to a similar moment in Princeton’s famed 1996 victory over #1 UCLA, which turned on what Miller called “the most famous and important pass in Princeton history.”

I’d like to start one of those fun, respectful arguments which, thank God, American sports still allows for in a way that, alas, everyone says American politics does not.

Miller is a professional sportswriter for a great newspaper. I am not even much of a college basketball fan anymore. And I’m surely not a historian of Princeton basketball. Although, knowing Princeton, they probably have an endowed Franklin C. (Cappy) Capon Chair for the Study of Princeton Basketball.

But I don’t think that the Arizona, Missouri, or UCLA victories, the 1998 UNLV win, or even the 1989 defeat to Georgetown, which ended with a Hoya fouling Kit Mueller on a shot at the buzzer, and was in some ways the most riveting of the famed Princeton NCAA performances, represent the most important performances in Princeton basketball history.

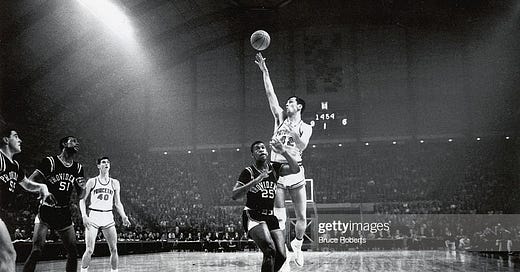

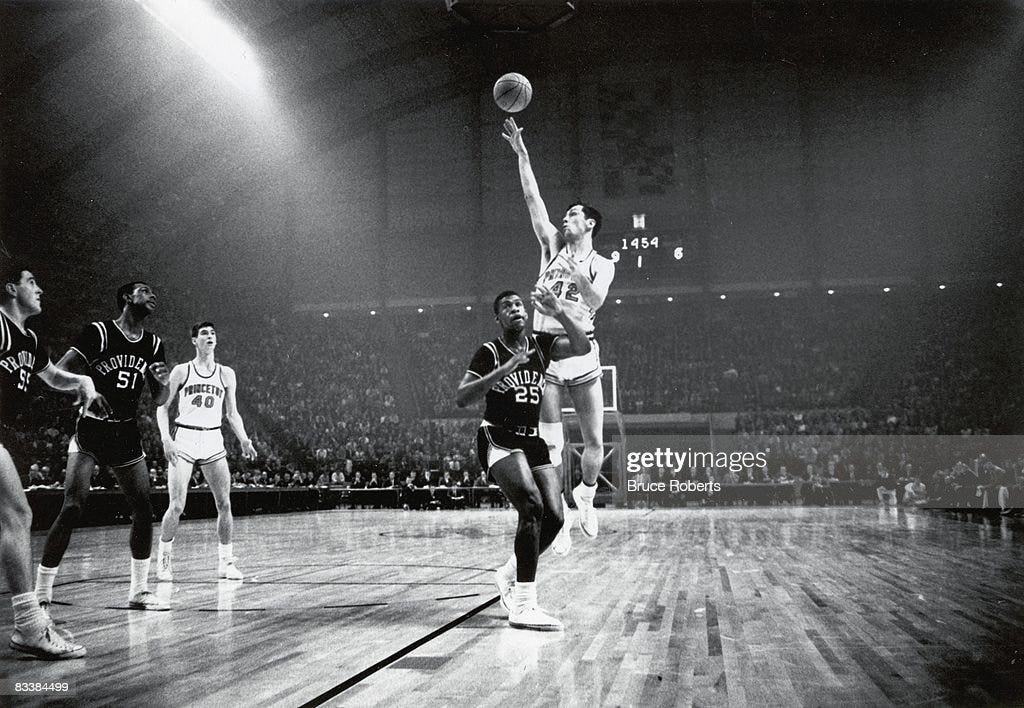

I believe that you have to look to 1965, to the Eastern Regional finals, when Princeton defeated Providence and qualified for the Final Four. Two reasons: First, Providence was in the class of those UCLA, Arizona and Georgetown teams. Second, the performance of the Princeton team was unlike any of the more recent NCAA victories, both in quality and meaning.

It's important to note that in 1965 this was a very different sport. Everyone—everyone—wore white canvas Converse All Stars (except those who played for iconoclastic coaches who put their teams in black canvas Converse All Stars.) Players wore “sweat socks”—the tube sock hadn’t been invented—usually two pairs to guard against foot blisters from those Cons. Some teams wore spiffy team-color-striped socks made by Wigwam Mills in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Shorts were short often with a little metal belt buckle at the waist. Haircuts were short by coaches’ mandates. If anyone had a tattoo you surely couldn’t see it on your black and white TV set. Coaching staffs were overwhelmingly white, so were some teams, and the historic Texas Western victory of an all-black team over all-white Kentucky was still a year away. Players were thinner, and few lifted weights. Watch old film and basketball appears much more genteel than today’s physical, emotionally honest, perform-for-the-audience game. There was no talk of paying athletes, although this being American college sports, that happened at some schools in violation of NCAA rules.

https://www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2021/03/moments-in-march-bill-bradley-led-tigers-final-four-run

The NCAA tournament was small and there was no hint of Madness about it. If you won your conference in the regular season you represented it in your own geographical region. (The ACC and the Southern Conference were exceptions. They ran conference tournaments to determine their single representative. “Independents” who belonged to no conference could receive “at large” bids.) As Ivy champion, Princeton played in the Eastern Regional; they only crossed the Appalachians when they headed to Portland for the Final Four.

Providence entered the Eastern Regional final a heavy favorite, and with good cause. They came in with a 24-1 record and had ravaged the independents of the northeast, many of them urban Catholic universities with great basketball traditions. Providence had a respected coach in Joe Mullaney, plus the wonderous Jimmy Walker, who went on to fame with the Detroit Pistons, Dexter Westbrook, and the scrappy Mike Riordan.

Princeton had a great star in Bill Bradley, who had brought his team excruciatingly close to victory over Michigan and their star Cazzie Russell before fouling out in the Holiday Festival final in Madison Square Garden in December. But Bradley aside, Princeton appeared to be just a very good Ivy League team, playing league games on Fridays and Saturdays (so as not to cut into weeknight study time) and feasting on Harvard, Dartmouth, Columbia and company. Providence, ranked #4 nationally, had every incentive to defeat the Tigers and get to Portland, where they could stake their claim to greatness against the likes of Michigan and a John Wooden-coached UCLA. Working class down to their black game uniform T-shirts, they might have had extra incentive taking on students from an elite university.

And they were pretty sure they had it in the bag. John McPhee reports in A Sense of Where You Are that the Friars had attended Princeton’s desultory regular-season victory over Brown in Providence. Some had publicly registered their amusement. They entered the game confident that Princeton’s early-round victories over Penn State and North Carolina State carried little significance. Perhaps this was why they took scissors to the nets after defeating powerful St. Joseph’s in the Eastern semifinal. Lightly regarded Princeton faced a powerful opponent, just as subsequent Princeton teams would open the tourney facing long odds.

But this was not a first-round game. It was for a spot in the national semi-finals. The winner would be one of the four best college teams in the nation, not just a second or third-round opponent for a fellow survivor. Whoever won had a legitimate chance at the national championship.

And Princeton smashed Providence. As McPhee describes it, everyone on the floor played like Bradley. With eight minutes to go in the first half, and Princeton ahead 27-24:

Haarlow hit one from the corner. Bradley hit an eight-foot jumper. Bradley hit a twenty-foot jumper. Hummer went two-for-two on the foul line. Walters hit a fifteen-footer. Rodenbach hit a fifteen-footer. Bradley hit a ten-footer. Haarlow went two for two on the foul line. Hummer scored on a drive. With eleven seconds to go, Bradley, on his way to the locker room, stopped, turned, and hit a twenty-five foot jump shot. The halftime score was Princeton 47, Providence 34.

The second half proved even more lopsided. Final score: Princeton 109, Providence 69. Frank Deford, a son of Old Nassau, wrote for Sports Illustrated that on that day, Princeton University had the finest college basketball team in the nation. (As a team, they had shot 63% from the floor.) Bradley, who had been raised as a high achiever, the recognizable kind of young person who may have sacrificed no small amount of joy in the pursuit of excellence, told McPhee, “It was the happiest I have ever been in my life.”

https://www.gettyimages.in/detail/news-photo/eastern-regional-playoffs-princeton-bill-bradley-victorious-news-photo/83384465?adppopup=true

Princeton hadn’t won this game with the now-familiar mix so beloved of David-and-Goliath addicts, of back-to-basics high school coaches, of middle-aged white men who were too lacking in athletic skill to get too far in basketball. They hadn’t won it with now-familiar Princeton attributes: the maddening patience; the cloying defense; the startling backdoor cut off a rope-a-dope ten straight perimeter passes; the well-timed three-pointer. This was not a game in which some national powerhouse struggled to extricate themselves from a 50-point game inflicted on them by the Tigers.

Princeton had scored 109 points and beaten the erstwhile best team in the east by 40.

They would go on to Portland and lose to Michigan again, with Bradley again fouling out. In the consolation game, another relic of the times, Princeton beat Wichita State to finish third in the nation. Bradley scored 58 points in his final game in a Princeton uniform.

Some would argue that the more recent victories over UCLA and UNLV, Arizona and Missouri, were more important wins. They would point to the massive growth of the sport, the media hysteria, the strength, speed, and abilities of a group of players no longer inhibited by the racial segregation that denied gifted black players opportunities in ways obvious (at southern state universities) and less overt (the unwritten taboo even in the north of playing too many Black players at once, broken but not killed off by Texas Western in 1966). International recruits, modern nutrition, strength training and video analysis all make Princeton’s victories over contemporary resource-rich Division I giants impressive and important, important at least in one university’s glorious basketball history. No argument there; these have been major achievements for all involved. And if this Tiger team continues its run, I’m ready to revise my thesis.

Nonetheless, the 1965 Eastern Regional final victory, over a strong opponent, by an overwhelming margin, in which Princeton demolished the #4 team in the nation, scoring almost at will while denying that team a final four spot to claim one for itself deserves the title of Princeton’s most important game. It gained Princeton basketball, and its greatest player, a storied place in college basketball history.

(And a coda:)

Bradley would famously matriculate at Oxford, turning down the New York Knicks’ generous offer, then return years later and become an important starter for two Knicks championship teams, then run successfully for the US Senate from New Jersey and contribute to the making of policy as a Democrat who could work with Republicans during four presidencies. He ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for president in 2000. I mentioned his name to two former students, devoted interscholastic athletes, New Jersey high school seniors, exceptionally bright, well-informed students headed to prestigious institutions of higher learning later this year.

They had never heard of Bill Bradley.

Notes:

John McPhee, A Sense of Where You Are: Bill Bradley at Princeton.

one of the great moments in Princeton Bball history. have added to my very long list